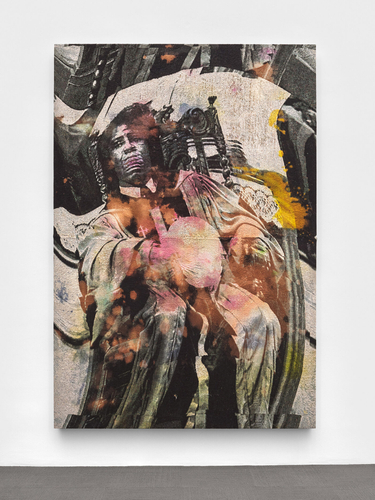

Noel W Anderson

We Give ’Em Reverend Brown

2023

Discharge and dye on distressed stretched cotton tapestry

110 × 75 in

Photo by Olympia Shannon. Courtesy of the artist.

Several years ago, I visited the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts’s open studios. I wandered into the studio of an artist deep in conversation, which blessedly allowed me to just look at the work. There was a huge tapestry that evoked a documentary, black-and-white photograph of police officers brandishing their guns while Black men stripped down to their boxers stood against a wall with their arms raised. However, the image was twisted in an s pattern as if the television set transmitting it couldn’t quite get the signal right. After looking, I managed to sneak in a greeting and get the business card of the artist, Noel Anderson.

His textile haunted me. I easily recalled his work when in the autumn of 2023 a press agent invited me to see his show at the Borough of Manhattan Community College. At the time, I was co-curating a show on sports titled Get in the Game at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and his work was completely apropos, but I saw it too late to get it on the checklist. That missed opportunity also haunted me. But lately I thought I’d like to speak with Anderson about what he’s doing and how the work is important to him. He couldn’t know this, but we are kindred intellectual spirits. My photography work in graduate school also explored the performance of Black masculinity, though not with his piercing insight.

—

Seph Rodney

Is part of your aim to make the ways in which Black people are distorted through televised media more legible by distorting the image yourself and making it obvious that these images are most often mediated?

Noel W. Anderson

A portion of the search is to acknowledge and repurpose the function of distortion inherent in screen-based imagery: televisual, telephonic, computer, cinema, lens, and so on. Prior to sending the digital file to the weavers, I torque the source image. Manipulating the image from within intimates the biases encoded in pictures. Warped and bent images arrive from a healthy suspicion: Ain’t it all skewed? Don’t none of this “appear” stable? Assuming that all screen-based images are mediated, thus manipulated, Die Leitung—meaning “the line,” “the management,” “the guidance”—is a German term that urges me to linger on how we are organized and disorganized through images and their agents. The tapestry is woven from a photograph that appears to tell us about ourselves. On the right is a lineup of Black men stripped and handcuffed in a disorganized organization vertically held by the slanted rigidity of the centrally located Black cop’s erect gun.

In Die Leitung (2016–20), the warped and wobbly weaving mimics the aesthetic of a TV experiencing an uncontrollable image as a scrolling picture. Termed “vertical roll,” this form of distortion occurs when there is a loss of synchronization between the incoming signal and the TV’s internal circuitry, which results in a continuously scrolling image. It might perhaps be helpful to think about Joan Jonas’s Vertical Roll. As a child of the ’80s, I experienced the magic in deploying rabbit-ear antennas in stabilizing the family television. When my civil engineer father would code-switch from the performance of perfect elocutionary English to command, “Boy, go fix that,” I would move those rabbit ears around to conjure some semblance of stability on the screen. As an adult, I interpret this failed synchronization as miscommunication and a gap within the process of representation. Ain’t it all skewed? Don’t none of this “appear” stable?

And it is that fugitive image that flaunts flexibility that arrests me. Distortion is a liberation that reveals that other things can be seen/scene. Torqued to the perfect tension, Die Leitung transforms the Black body into a question mark, challenging many assumptions historically entangled in the woven flesh of representations of Black performance.

SR You’ve told me that a question no one ever poses to you is: “What does it mean for a Black man to create weavings and tapestries?” My question is whether or not it is important to you that your tapestry work be associated with femininity or domestic life? Do you want to challenge this association, and what would a successful challenge produce?

NWA Those same corporeal expectations extend to me, the maker. The sports announcer exclaims, “He’s a beast! He’s a dog!” The image of the Black male weaver is excluded when tapestries are framed by racist tropes of animality against the tradition of “women’s work.” Qualified by gender, textile associations include aspects of care: maternity, quilting, domesticity, and so on. I want to acknowledge this contradiction as a way to include Black men in this discourse. Huey Copeland calls it “tending-towards-care.” Here we can adapt it as “mending-towards-care.”

SR In your King/zzz (2020–21) tapestry, there is an image of Rodney King with his face distorted in a way to make him look injured; and in an adjacent image, Martir (2020–21), four smiling white police officers are carrying something that might be a body in between them. Both images are obscured by colorful stray bits of cotton picked from the underlying material as if they are under a shower of confetti. Are you suggesting that moments of the mobilization of state power to brutalize Black people are also perhaps moments of public celebration? If so, is this celebratory attitude an inevitable byproduct of living in a society that flocks to the spectacle?

NWA In my hands, images are on the mend. King/zzz is a photo composite of MLK Jr. and Rodney King. I rework the surface and fibers of the woven cotton tapestry in an attempt to symbolically care for both men. Surface interventions, including abrasion and pulling cotton threads, which is an allusion to picking cotton, are intended to manifest the capacity of Black concern. This sense of loving address is successfully present in the confetti-like quality of the pulled threads dangling from a tapestry like Martir. The image is from the infamous photo of the Chicago Police Department removing the body of assassinated Black Panther Party leader Fred Hampton from his apartment. Apocalyptically framed by four grinning cops, the confetti-like protruding threads celebrate the care and attention I critique and think we should have for images and each other; it’s the same level of concern Hampton had for his people.

SR With the Make Me Come Out Myself (2022–23) series, you have small, plastic figurines designed to represent Black basketball players. You have seemingly melted one and reconfigured it so the head appears to be emerging from the back of the torso. The Black athlete is a hypermasculinized version of a US-American conception of masculinity that this work remakes as an agonized, unworkable, and even inhuman model. Do you think that the figure of the Black, physically gifted athlete is more accurately perceived as such?

NWA The toy figurine sculptures entitled Studies for Black Exhaustion (2022) are from my exhibition Make Me Come Out Myself. They question the inhuman and superhuman expectations historically projected onto Black bodies. Black subjects, and athletes in particular, navigate a world assuming their bodies are supposed to be able to perform superhuman feats—jump the highest, run the fastest—that are the legacies of slavery and the extension of racial terror post-Reconstruction. Ain’t it all skewed?

The intervention-distortion is chemically induced. The figurines are collectibles from a brand called Starting Lineup. I soak the toys in a chemical bath that alters the rigid structure and makes the figurine more malleable. I can then torque the torso, bend the limbs through the body, and, as you noticed, push the head through the backside. Blended with humor and wonder, I mean these sculptures to illustrate the absurd expectations and assumptions central to the infrastructure of the society of the spectacle.

SR How does work in your current show, Black Excellence, deepen or extend the issues you have been wrestling with, such as public perception of Blackness, masculinity and its performance, the meditation of public images, and more?

NWA The exhibition and its catalogue extend my pursuit of the function of distortion in the production and circulation of images of Black masculine performance. The exhibition is a collection of old and new works that service a conversation about the requirements—or expectations?—placed on Black bodies and subjectivities by the pursuit of racial success.

The inventory includes erased Ebony works, stretched and suspended tapestries, and a brand-new video project. The first-floor houses tapestries, and works on paper push the critique of expectations inward. In this space, a work like Battle Royale (2023)—a large diptych depicting two basketball players being pushed back onto the court by white courtside fans—questions the expectations Blackness places on itself. The second floor holds tapestries and objects from the police series—think Die Leitung. I’m hoping that in conversation, these appositional efforts work to interrogate the term excellence. What are the conditions of its achievement? What are the mechanisms of its miscommunication and miscommunication? How can they be exploited? What seems/seams stable ain’t always so.

Noel W. Anderson: Black Excellence is on view at the University Art Museum at the University at Albany, New York, until April 3—Seph Rodney